“Have courage, and be kind.”

This sentiment recurs throughout Disney’s new live-action Cinderella. From the moment Ella’s dying mother offers her this advice, it becomes the driving force in Ella’s life and the through-line in her characterization by actress Lily James.

Imbuing Cinderella with courage and kindness has a purpose: Director Kenneth Branagh uses it to give 2015’s Cinderella more agency than her cartoon predecessor from 1950. After all, in the broader media culture, bold, empowered young women are on trend (think Frozen’s Anna and Elsa, Brave’s Merida, and The Hunger Games’ Katniss Everdeen). Passive victims like Cinderella, Snow White, and Sleeping Beauty are passé, out of step with modern values.

In Branagh’s retelling of Disney’s animated classic, then, Ella makes a courageous choice to stay in her father’s home with her stepfamily. She chooses to respond to their cruelty with unearned kindness, even when they eject her from her room, stop feeding her properly, force her to tend an estate once managed by many servants, and taunt her, calling her "Cinderella" instead of Ella. Because it is her choice, the film positions Cinderella is not merely a passive victim, but a young woman with agency.

Young women’s agency is a hot topic. Parents, critics, and members of the pro-girl-empowerment community want girls to grow up to feel they are in charge of their own lives. As presented in Cinderella, however, Ella’s choice to submit graciously to abuse is a problematic message that weakens the film. If Ella’s courage and kindness lead to abuse and deprivation, what good is it?

Here’s the underlying problem: All choices happen in a context. In the cultural context of Ella’s (vague and undefined) historical era and geographic locale, what range of choices would a young woman in her position really have? Could she have chosen to leave her family home if she had wished to? Did she have any extended family to go to? With her skills and mannered upbringing, could she have pursued employment as a lady’s maid, or would that not have been appropriate for a young woman of her station?

None of these questions are addressed in the film, which is unfortunate. It would have been easy enough to address them in the market scene, where a former servant of her father’s household asks Ella why she stays with her stepfamily. Her answer makes little sense: She states that she promised her parents to always cherish the family home, and so she stays. It’s a strange answer, for surely her devoted parents would never have wanted her to value a mere building more than her own health and well-being. From a storytelling perspective, it’s truly an opportunity lost: A quick conversation on the constraints Ella faced as a young woman alone in the world would have strengthened the film, giving it more power. As Joanna Weiss points out in the Boston Globe, “An easy answer, had Disney chosen to give it, is history. Unmarried women weren’t always free to move out on their own. Say that out loud and spark millions of deep conversations in minivans on the ride home.”

The long and short of it is this: While Branagh presented Disney’s newest Cinderella as less of a victim because she made a courageous choice, her choice was merely choosing which way she would endure her abuse. What were her options, really? To endure her situation with grace, or anger, or despondency? Agency of this kind is incredibly limited, and Branagh’s inattention to the cultural context of Cinderella’s world is a weakness of the film. Accepting one’s victimization does not make one any less of a victim, even if ultimately you do so with such grace and dignity that you are a fit bride for a prince. Ultimately, Cinderella still requires the interference of a prince to change her fate from that of a victim.

In interviews, however, Branagh and his cast have asserted that Cinderella’s relationship with the prince was irrelevant. As Richard Madden, the actor who played the prince in the new film, stated in an interview: “This young woman in distress doesn’t need a man to save her. That’s totally irrelevant—she’d be fine without the prince, she’d get on with it.”

This sentiment sounds wonderful, but the film offers no indication that Cinderella would have “gotten on” with any other life kind of life. As long as her stepfamily was around, she seemed destined to remain a quietly courageous victim engaged in no better than slave labor. How would the continuation of that status quo have been “fine"?

Viewers may be also frustrated by the abruptness of the Fairy Godmother’s bumbling-but-good-natured intervention. (Aside: Why did this film and Maleficent reimagine fairies who were portrayed as competent, powerful, gray-haired older women in the original animated films as younger and ditzy?) She only shows up when Cinderella wishes to attend the ball, but Cinderella needed so much more so much earlier. Is this further evidence that in her socio-historic context, Cinderella’s choices would have been so limited that her only real “choice” was to stay with her abusive stepfamily or find a man? It seems all the magic in the world could not afford her a way to save herself. The best it could do was to help Cinderella deliver herself into the arms of the most eligible, handsomest, near-stranger bachelor around.

The prince seems to be drawn to Cinderella’s personality, her passion for courage and kindness, more than her beauty. It’s not a love-at-first-sight tale, but rather, one of love at first meeting, first conversation. Their first encounter is in the forest, when neither knows anything about the other. Cinderella loves animals (she is a Disney Princess, after all), so she chastises her new acquaintance for hunting a stag. The prince, in turn, is taken by Cinderella’s words and spirit. The idea that he is drawn foremost to her personality is a step in the right direction for Disney, which tends to over-emphasize the perceived value of its heroines’ appearances.On the other hand, though, viewers may be pleased with subtle but important changes to the prince’s storyline. Some good points:

- The prince has a close relationship with his dying father, who calls him Kit (which is very sweet), and who on his deathbed gives him his blessing to marry for love rather than political advantage. Father-son relationships are rarely depicted in Disney films, and this backstory is refreshing.

- The prince knows that the “mystery princess” from the ball was the girl he had become smitten with in the forrest. He recognizes her, and that—not her physical appearance—is why he seeks her out to dance.

- After Cinderella leaves the ball without revealing her identity to the prince, he sends an announcement to every village, declaring that he invites the “mystery princess” to join him at the castle so that he may propose to her, if she is willing. But she does not join him at the castle. He wonders whether she was somehow prevented from accepting his invitation, so in an effort to ensure she has a choice in the matter, he launches a search for the woman who fits her glass slipper. In an interesting twist, the glass slipper is not actually necessary to identify Cinderella, as the prince has seen her in both commoner and princessly form. Rather, the slipper serves as an excuse for his staff to approach every maiden in every corner of the kingdom to ferret out the one he is seeking, wherever she may be, and give her the option to accept or decline his offer of marriage, without the interference he worries may be at play.

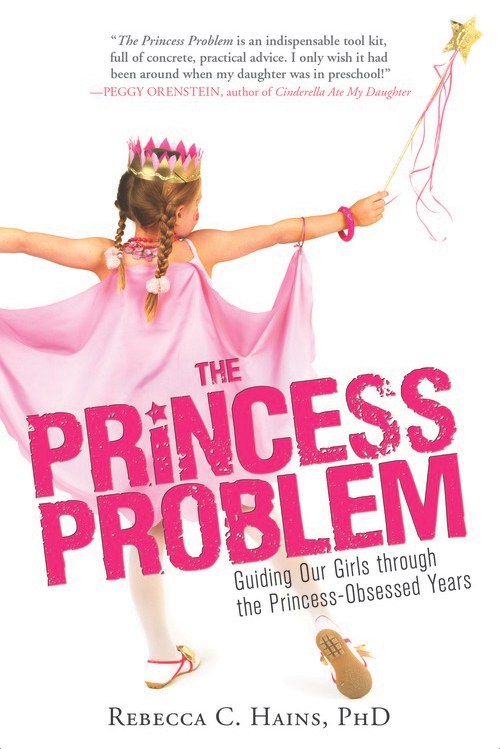

Read more from the author about how to raise empowered girls in a princess world in her book The Princess Problem

Like other parts of Branagh’s Cinderella, then, the prince’s search positions Cinderella as having a choice, as having agency in the matter. Unlike the stag the Prince was hunting earlier in the movie —which I read as a parallel to the beautiful maiden the prince was essentially hunting in Disney’s 1950 Cinderella — today’s Cinderella is not a prize to be won. She is treated by the prince as a person in her own right and he appears to take her wishes into consideration, aware of the possibility she might decline to be with him.

Realistically, of course, if we consider the significant matter of context, it’s hard to imagine her choosing the alternative. Why would she continue to be abused, with no exit strategy possible, when she can leave her abusers and become a princess?

Nevertheless, the idea that the Prince recognizes Cinderella’s agency and hopes she will choose him, rather than assuming that she is there for the taking, is perhaps the most important revision to the film. The theme of courage and kindness fall flat, but the fact that the prince does not feel entitled to have her unless she consents is a meaningful improvement to the story.

After all, girls are not prizes to be won by male suitors. They’re people.