Photo:

Credit: Will Austin

Jenny Lisk’s self-described “perfectly normal” life — a successful career as an IT professional, husband, two kids, a dog — altered irrevocably one Friday night in the spring of 2015 when her husband Dennis mentioned that he had been experiencing bouts of dizziness that week. Concern mounted over the ensuing days, as he began exhibiting signs of confusion and forgetfulness.

Read more from Jenny Lisk:

What I’ve Learned About Widowed Parenting

25 Practical Ways to Help a Friend Through the Illness or Death of a Spouse

A visit to the clinic and an MRI later, the couple received devastating news: Dennis had glioblastoma, an aggressive, malignant form of brain cancer. An expedited surgery two days later was followed by eight months of “playing defense” against the deadly disease — after rounds of chemotherapy and radiation treatment and blocking and tackling on additional complications, Dennis entered hospice care at home, where he died in January 2016.

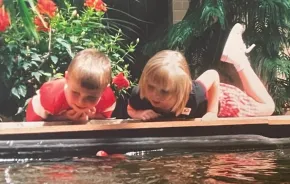

The newly widowed Lisk was left to pick up the pieces, with an 11-year-old son and a 9-year-old daughter relying on her to carry on. She recalls thinking, “Now I am in a new job: I’m a widowed parent. What do I need to know? What do I need to do? I’m the only parent now of these kids. How do I do this so I don’t completely screw them up?” Lisk quickly figured out that there was no “What to Expect When You’re Widowed” guide to navigating life following the death of a spouse, particularly with respect to the experience and responsibilities of being a solo parent.

She decided to go looking for answers — for herself and for all grieving families coping with similar losses. In November of 2018, Lisk launched “The Widowed Parent” podcast, a guide to the “murky waters of ‘only-parenting’ after the loss of a spouse.” Her podcast journey will provide the basis for an expert-informed guide to widowed parenting the likes of which she wanted so desperately to find when she first became widowed at the age of 43. She is also presently writing a memoir based on her family’s experience.

We caught up with Lisk to learn more about her mission to help widowed parents and their children thrive in spite of their traumatic loss.

What motivated you to create “The Widowed Parent” podcast?

I’m not saying it’s easy by any means, but I think there’s a lot of really good resources for adults in their grief. And then there are a bunch of people doing really good children’s grief work. But I think there’s a gap in the parenting piece. How do you as the surviving parent help your kid? And backing it up before that, how do you, as the parent with a terminally ill spouse, begin to help the kids understand what’s going on. Because you know how the story is going to end: The terminally ill parent at some point is going to die. How do the surviving people in this family not “die” along with them? And I don’t mean suicide-dying. I mean how do you somehow not become completely destroyed, and not live your life while you’re still living your life?

I realized that a podcast is a really accessible format that I could use to go out and interview people who had pieces of information and perspective and advice and knowledge and whatnot on all these pieces of the puzzle. So, I interview a new person each week about a different theme, question, topic or challenge, and then bring what I’m learning to other people like me.

How do you articulate the mission of what you're doing?

I’m really focused on how widowed parents can work to increase their family’s wellbeing. There are multiple facets to that: It’s about addressing the grief piece and any other mental health issues that arise; it’s also about helping them in their role as the only parent. What it comes down to, really, is that I think all kids deserve a chance to thrive, including those who’ve lost a parent.

But it’s hard: When you need to tackle some big parenting challenge, you’d like to think you can come at it when you’re at your strongest. But in this case, [the widowed parent is] coming at it when everybody is at their lowest.

The surviving parent is really the key factor, I think. I’m not saying that they might address everything themselves, but they can bring in the right resources and they can bring in the right support. They’re the center, the linchpin. Plus, they’re modeling for their kids: How they handle grief, how they handle emotions, how they handle decision-making, problem-solving, all the things that parents do for their kids every day.

Was there anything that helped you and your kids begin the process of coping with the situation and your grief?

I got some advice early on to be honest with the kids, as honest as possible. It’s really hard to know what to say or do, or how to approach it, because you want to protect the kids. Sometimes it seems like shielding them from hard things is the best way to protect them. But it turns out that’s actually not the best way to protect them.

What I’ve learned from my own experience, plus all the interviews I’ve done for the podcast, is that it’s actually better to be honest with them and then deal with the hard questions and the hard emotions and all that than it is to try to hide it somehow. If you aren’t honest, two things are probably going to happen: First of all, they’re going to come up with maybe an even worse scenario in their minds. Secondly, it’s actually really critical that the kids be able to trust that surviving parent. And if they’ve given them the wrong information, or withheld something, then that bond gets broken or damaged in some way, and that is going to be worse for the kids overall.

In hindsight, I’m glad that I got some of that advice to be honest, and the encouragement to tell as much as I knew. It’s always okay to say, “I don’t know.” Because sometimes I think parents believe that if they don’t know all the answers, they can’t have the conversation yet. It’s so much better to say what you do know, and then keep the conversation going.

Have you discovered any particular strengths emerging in yourself that maybe have surprised you?

I don’t know if this is exactly answering your question, but I find that I’m actually really enjoying working on this podcast and all the related research. Maybe it sounds weird that doing interviews with people about grief and difficult topics is fun. But I feel like my world has expanded from a very narrow focus on internal corporate IT work to this world where I talk to interesting people and I’m learning things all the time.

Every week is a different topic, and I kind of categorize them in three groups of people that I interview. One is experts, people who’ve written the books or run the grief camps or the grief centers. Another is widowed parents who are seasoned, if you will. They’re down the road a little bit, and they can reflect on their journeys.

The third category is people who are now adults and who have lost a parent when they were a kid or a teenager. As a parent, I have talked to some of my guests who are now 25, 35, 45, and they lost somebody when they were 3, or 11, or 19, to hear what their journeys were like, and what was hard for them and what they felt misunderstood about, and what was or was not helpful to them at home, at school with friends, with whatever.

Why do you think that resources for supporting widowed people in parenting grieving children are lacking?

Believe it or not, there’s not much academic research on this topic of widowed parents and their needs and challenges. Fortunately, there are a few things going on that are increasing the attention, which is good. One of them is Sheryl Sandberg’s journey and her book “Option B: Facing Adversity, Building Resilience and Finding Joy.” It seems like we are on an upswing of attention in this area. I also want to stress that there are people doing good work, in lots of different areas and ways.

I recently interviewed the CEO of the National Alliance for Grieving Children for an upcoming podcast episode. She actually said that the field of children’s bereavement has really only been coming together as a field in the last 20 or 25 years, and [those working in the field are now] asking, how do we as a field address this in ways that are effective and appropriate, and how can we share best practices?

[There’s an organization called] Judi’s House in Denver, and they have this thing called the Childhood Bereavement Estimation Model. It’s really fascinating. The number one conclusion of the study is that one in 14 children in the United States will experience the death of a parent or sibling before they reach the age of 18. They’ve broken it down by state, as well. Washington state, I think, is a little bit better off than that, but not dramatically better.

Part of the problem they’ve identified is that in terms of getting support for grief, there’s the peer model, such as a grief center with peer counseling. Then there is the “medical model,” where you have to have a diagnosis. Grief is not actually something that insurance companies will pay for counseling for. So, you have to wait until it gets to the point where you’ve suffered so much that you’re diagnosable as having an anxiety, depression, or this or that. And now we will pay for you to get help. But what if you’d gotten support at age 19, 20, 21?

It’s exciting to see the things that are starting to happen, and it’s exciting to be in a position to be able to touch all these people. It’s rewarding, and it’s actually fun.