I can still feel his finger inside me. If I think about it. Which I try not to.

I was 9 years old. I couldn’t fathom why anyone would want to put their finger inside me, so I wasn’t repulsed, just confused. And it was quick, so quick I can’t believe I can recall the vile sensation more than 30 years later.

I’ve never considered myself a survivor of sexual assault. I didn’t think that brief moment defined me. And yet, each new story of a famous man abusing his power pulls my focus from whatever task I’m supposed to be accomplishing. I have to wonder, what would be different if that man hadn’t violated me?

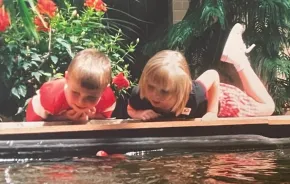

I was in the swimming pool at the college where my father worked. My older brother and I were playing in the shallow end. I was practicing underwater flips because I liked the way the water felt around my body as I twisted through it. Then I moved onto handstands.

I grew up on that campus and was allowed to roam freely, but it was also the age of “Stranger Danger.” As kids we were taught to “Run, Yell, Tell,” right along with “Stop, Drop, and Roll.” We all knew the story of Adam Walsh, the 6-year-old who was kidnapped and murdered in Florida. I can still picture the photo of him with his red baseball cap and bat. When my cousin and I walked from her house to the local strip mall to spend pocket money on makeup and hair ties, we held hands as we ran past the windowless white van that was always parked in her neighborhood.

The problem with a steady diet of fear meant to protect you is that it puts the onus of safety on the potential victim.

We were raised on a steady diet of fear. We were taught not put ourselves in situations where we could be harmed. But when the man approached me and my brother in the pool, no alarm bells went off.

He looked like all the other students on campus–some were our babysitters, some were my brother’s soccer coaches. The man talked to us for a bit as we splashed around. He told me my legs could be straighter in my handstand. To prove him wrong, I dove under the water, planted my hands on the pool floor and pointed my toes towards the concrete ceiling. The man gripped my thighs and straightened my legs. Then there was something inside me. When I remember it, legs crossed as they are as I write this, I think of it as a knuckle. I really have no way of knowing if it was a finger or a thumb.

As soon as I could flip my body over, I told my brother it was time to leave. To his credit, he didn’t ask questions, he just followed me out of the pool. I never told my parents, despite having a close relationship with each of them. I never understood why I kept it from them until this most recent rash of allegations against high profile men.

My parents taught me how to keep myself safe. Of course they did, they loved me. But they never told me if I got hurt, it wouldn’t be my fault. That day in the locker room, as I changed quickly into my dry clothes, I imagined the questions; I asked them myself. Why was I talking to someone I didn’t know? Because I talked to people every day who I didn’t know, I was friendly. Why did I let someone I didn’t know touch me? I didn’t know he was going to until he did.

The problem with a steady diet of fear meant to protect you is that it puts the onus of safety on the potential victim. But it’s more than “victim blaming” because it starts long before a violation occurs. “Stranger Danger,” despite John Walsh and our parents’ best intentions, became its own kind of victimization.

In the aftermath of sexual abuse, assault or harassment, when victims speak out, they are asked why they are making a big deal. When they don’t speak out, they are faulted for letting a criminal harm someone else. When they speak out “too late” they are asked why they didn’t speak out sooner? All of these demeaning replies center on the response to the violation and not the violation itself. For anyone raised at the height of “Stranger Danger” the groundwork for this kind of blatant “missing the point” was laid when we were kids.

As a parent, I want a safe, healthy life for my kids. What parent doesn’t? We’ve talked about how to respond if someone they don’t know approaches them. We’ve talked about what to do if they get separated from us in a crowded place. We use proper language to talk about the parts of their body and we tell them they don’t have to hug anyone they don’t want to. But in response to my realization that I had been blaming myself for being sexually assaulted at 9, I’ve added a new line to our parenting arsenal.

“If someone hurts you,” I told my 8-year-old daughter, “it’s not your fault. People make bad choices and their choices are not a reflection on you.”

She looked at me blankly the way she does sometimes when I introduce a new concept. When I asked her if she had any questions she shook her head. She knows this won’t be the last time she hears about this, but she probably doesn’t know how hard it was for me to say.

I’ll never know how much of what followed in my life is a result of what happened in that pool, but I do know this: At 9 years old I had already internalized the message that when a man violates you, it’s your fault. Very little in my life has contradicted that, but I’m determined my kids won’t feel the same way.

This essay originally appeared on Motherwell.