It happens nearly every day when I pick up my children from school. As I wait in the hallways and chat with the other parents, some child will walk past me and stare at my hand. Their faces grow serious. They stare without blinking. And they are so lost in their confusion that they don’t see me looking back at them, waiting for a reaction.

I was born with no fingers on my right hand. The teasing started in third grade. Once puberty hit, I started hiding my hand in the sleeve of my long-sleeved shirts. I did it constantly, to the point where I wore sweaters at summer camp. But kids grow up, and by the time I got to college, people knew to keep the looks brief and the comments out of earshot. I grew up, too, and became confident in myself and at peace with the fact that I’m different.

Or so I thought.

I can always tell when another adult notices my hand for the first time. There’s that pause that’s one second too long to be a passing glance and one second too short to be a stare. But younger kids don’t know that they aren’t supposed to stare. I’ve seen more than a couple of children go into a trance, their eyes following my hand as though it were a hypnotist’s watch.

Parenting frequently makes us relive both the good and bad of our childhood.

In the beginning, I was able to laugh it off. But as my kids have gotten older, the stares have changed. There’s an understanding now that my hand is a “disability.” That it’s more than just different, it’s weird and even scary.

I know the thoughts behind those stares because I heard them when I was their age from the kids I went to school with. I’ve realized, to my dismay, that I have to introduce my disability to a whole new batch of open, honest and curious elementary school students — my kids’ schoolmates.

Parenting frequently makes us relive both the good and bad of our childhood. In this case, it’s forcing me to deal with issues of self-esteem, pride and difference that I thought I had conquered. It’s become a kind of midlife growing up. I have to stand up for myself and for every other disabled adult and child out there by being open about my disability and refusing to hide it.

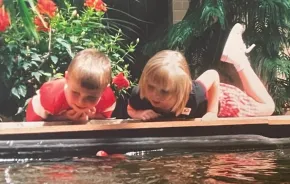

More than anything else, refusing to be ashamed of my hand is important because I’m a mother. It’s not just the eyes of those other children that are on me; it’s my children’s eyes as well.

My children see how I respond and how I hold myself in public. I have to push myself to be brave for them, not just to let them know that disabilities are nothing to be ashamed of, but to let them know that their mother loves herself — all of herself, unconditionally. Just like I love them.