Editor’s note: Science, technology, robotics, engineering, art and math: In our schools and communities, there is more demand than ever for STREAM. Yet only about a third of eighth-graders score “proficient” in math and science. In this ongoing series, sponsored this month by King's Schools, we’ll explore how schools and organizations are approaching STREAM in new, game-changing ways.

Editor’s note: Science, technology, robotics, engineering, art and math: In our schools and communities, there is more demand than ever for STREAM. Yet only about a third of eighth-graders score “proficient” in math and science. In this ongoing series, sponsored this month by King's Schools, we’ll explore how schools and organizations are approaching STREAM in new, game-changing ways.

In many ways he looks like a typical teenage boy: T-shirt and glasses, close-cropped hair and a casual smile. But when 14-year-old Cole sits down at a table with a therapist named Danielle and she begins speaking to him, Cole’s eyes quickly drift away. While Danielle tries to talk with him and keep his attention, Cole gazes off to the side and fiddles his fingers, not meeting her gaze.

Later, when Cole sits down across from a new friend named Milo, things are very different. Cole’s eyes are glued to Milo’s. He leans in, he nods, he answers Milo’s questions, raising his eyebrows and widening his eyes. When Milo lifts his arm in the air, so does Cole, never losing eye contact, a mirror of engagement.

Milo is a robot.

Two feet tall with a shock of chocolate brown hair and a friendly, open face, and wearing a gray spacesuit and clunky shoes, Milo is programmed to speak 20 percent slower than most humans and to prep his friends with explanations of what is coming next.

“Today we are going to learn about saying ‘Hi!’ Smile and say ‘Hi!’” he says in a video from RoboKind, Milo’s manufacturer.

Milo and other similar adaptive and robotic technologies are rapidly becoming key tools in improving learning for kids who have autism, like Cole. With the patience to repeat things as many times as necessary without frustration, and the programming to adapt to the needs of his young human friends, Milo helps kids emotionally and socially connect and interact. Within this new landscape, technology is helping kids in therapy, in school and in life.

The robotics frontier

Under the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), created in 1975 and reauthorized in 2004, public schools must provide special education services at no cost to families with children ages 3–21 who have mental, physical and emotional disabilities falling into 14 categories. The goal of this mandated support, which served 6.4 million students in the U.S. in 2012–2013, is to help students achieve in school, life and work settings.

In recent years, the percentage of students served by IDEA who have autism has been on the rise — 7.7 percent of students in 2012–2013 had autism, compared to 4.5 percent in 2007–2008 — even as the number of total students served (which include those with intellectual disabilities, developmental delays, emotional disturbances and other disabilities) has stayed relatively stable. The act also covers students with hearing, vision and speech impairments and chronic health problems.

Typically, special services are carried out by school social workers or therapists. Now, these intervention teams are turning to a range of technology to better reach and teach kids with special needs.

Enter the devices.

In 2013, The New York Times reported on a young girl who had a chronic heart disease that weakened her immune system, forcing her to stay out of the classroom. She used a VGo telepresence robot, a robot that moved from classroom to classroom and which the 9-year-old South Carolina girl dressed in a tutu and controlled from her home computer, to attend class and continue her learning. Other school districts also have invested in these robots to meet the needs of students.

Robots are a subset of a growing technology toolkit being tapped for therapy and teaching. Tablet computers are increasingly being used by many therapists and teachers to help increase task completion by students with autism. A recent study reported in Learning Disability Quarterly found that iPads as an intervention, when coupled with instruction, served as a promising instructional method for fifth-grade students with learning disabilities. It also found that the iPads helped to improve math fact fluency.

Virtual reality (VR) is another treatment and teaching tool that is becoming popular. When Facebook purchased Oculus VR for $2 billion, Mark Zuckerberg announced that VR would have “far-reaching implications” for a range of applications, including classroom learning. A Florida State University study found that children demonstrated improved social competence, increased facial expressions with body gesture recognition and improved interactions during VR intervention sessions. Parents reported that they witnessed positive changes in their children as a result of the VR intervention.

The landscape of possibility for students with special needs has expanded rapidly, but perhaps one of the most exciting tools being studied and used is socially assistive robots (SARs). Autism therapy was one of the first applications of such technology.

Playmate and teacher

Autistic children can experience a variety of challenges in social interactions, such as difficulty holding eye contact, challenges making and reading facial expressions and struggles with other social engagement behaviors. They may have issues with attention and problems demonstrating shared interests. A robot is, in many ways, the perfect partner and can play many roles, from teaching to modeling behavior to mediating social behavior between the student and others. Mostly, however, a robot for a student with autism can succeed because it is a unique hybrid of human and machine: While it is not human, it can elicit human responses and interactions, often with fewer stimuli than humans create. This, in turn, helps students feel safer and less threatened during treatment.

At the McCarthy Teszler School in South Carolina, Elena Ghionis works with students with special needs and has been a certified autism spectrum disorder (ASD) specialist for 22 years. Along with Amy Fichter, a certified ASD specialist for the Chester County Intermediate Unit for Chester County Schools, Pennsylvania, Ghionis has been working extensively with Milo, a SAR that uses Robots4Autism, a research-based curriculum created for students with autism by RoboKind.

Ghionis, who works with kids ages 3–21, says that Milo creates a very important bridge between technology and human interaction. “A child can interact with Milo and play a game. Then Milo asks questions, and the child communicates with Milo. Milo will then answer the question or redirect the child,” she explains. Ghionis uses Milo to help teach students social, emotional and communication skills and also to help improve speech production for students who have difficulty.

Fichter, who works with kids ages 5 to 8, has seen her students get extremely excited when instruction with Milo begins, and she says they have demonstrated real success, including increasing the time that they are able to participate in lessons and increasing the number of lessons that they complete within a session. Thanks to Milo, family and staff members have reported that students are demonstrating these learned skills in school, community and home, Fichter says.

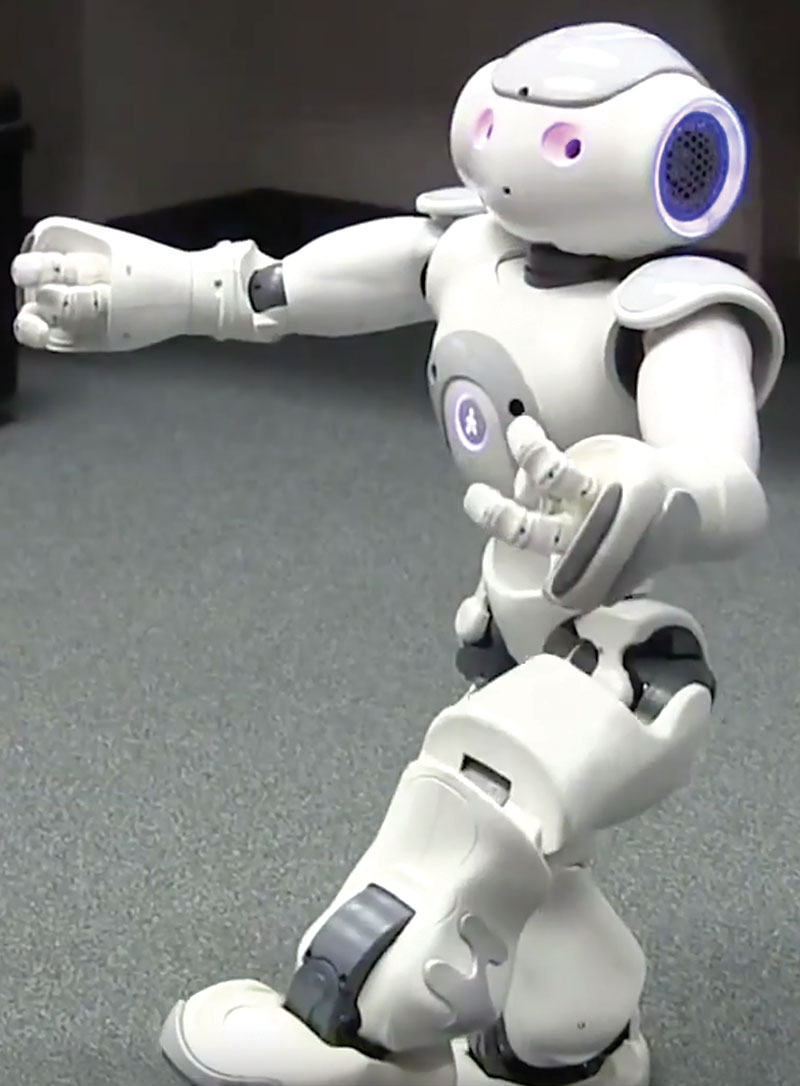

At the Daniel Felix Ritchie School of Engineering and Computer Science at the University of Denver, Mohammad Mahoor, Ph.D., is leading an interdisciplinary team of researchers in exploring whether the NAO (pronounced ”now”) and Zeno robots can improve communication and social skills of children with autism.

At 22 inches tall, NAO is a semi-autonomous humanoid robot with immovable eyes, which responds to voice commands, can dance and mimics human behavior. NAO is made by SoftBank Robotics and uses programming called Autism Solutions for Kids. Zeno is a 2-foot-tall humanoid robot with movable eyes, made by Hanson Robotics, a company known for its use of “frubber” skin, which contracts and folds much like human skin.

Working with 75 kids with high-functioning autism, ages 6–17, Mahoor’s team has studied eye gaze attention, facial recognition and emotional recognition skills with NAO and Zeno. With NAO and its immovable eyes, the focus was on children’s own gaze, says Mahoor. “Initially . . . the research question was how children with autism shift their eye gaze when they speak and communicate with people face to face,” Mahoor says.

Then the team, in conjunction with University of Denver’s Department of Psychology, used Zeno, with his movable eyes, to study how children with autism perceive or recognize other people’s gazes. These two studies are critical because they illuminate how children with autism can learn to focus, increasing their attention span with peers, parents and others.

Currently, Mahoor’s team is using the robots to focus on intervention, instead of trying to correct social responses, and teaching social and emotional recognition skills. “In some cases, parents have said that they have never seen their son hug a stranger, but saw him hug a robot,” says Mahoor. “Ninety-nine percent of the kids we studied liked the robot. They wanted to come back and play with the robot for more sessions.”

For infant and toddler patients who need pediatric rehabilitation for motor disabilities, such as cerebral palsy, a University of Delaware research team using NAO has developed the Grounded Early Adaptive Rehabilitation (GEAR) program. According to Herbert Tanner, Ph.D., the goal of GEAR is to program a robot specifically to be used in the rehab environment to boost motor exploration and coach a child through assisted mobility.

It would look like this: A child is secured in a harness much like a jumper swing, which lets them explore what they can do with their muscles while being supported. The device is coupled with sensors to monitor movement, and the child’s motion is recorded primarily by a network of surrounding cameras, which collects data from multiple perspectives, Tanner says. NAO can then be programmed based on information collected by the cameras and sensors, adapting its behavior to each child’s level of performance. This, in turn, gives caregivers the chance to create more personalized interventions. Tanner hopes that GEAR will work not only for institutionalized rehab settings, but for home use, too.

Not just using robots, but building them

Rather than using robots for treatment, some kids with special needs take robotics one step further. They build them. In 2015, Seattle teen Delaney Foster was a high school senior and member of the CyberKnights robotics team at King’s High School when she decided to find a way to help her sister, Kendall, also get involved in robotics. So Foster created Unified Robotics to welcome students with special needs from Roosevelt High School to work with King’s CyberKnights team. Every week during robotics season, the CyberKnights take a bus from King’s to Roosevelt to collaborate with the students there, who have a range of skill levels, to design and build robots.

At first, some students were hesitant about whether the program could work. Some of the students with special needs were nervous because they had never worked with robots before. CyberKnight students were concerned because they had never worked with students who have special needs. But by emphasizing fun and a motto of “no experience necessary,” a collaboration was built.

Adult mentor and Foster’s mother Nicolle Foster, says the program initially had 29 students participating from both schools. But by the end of the season, they had built six different robots and created eight teams of from two to six students who worked together to build a robot. The final competition, formatted like those on “BattleBots,” welcomed more than 100 people, who cheered the teams on. “NPR covered it. The community was invited,” says Foster. “It was so fun!”

The idea of connecting students with special needs with those who are typical learners is expanding to other schools, Foster says. She says 36 Pacific Northwest teams are interested in starting a Unified Robotics program and inquiries have come from as far as Maine, Texas, Canada and China. According to Foster, schools interested in starting a Unified Robotics club can receive support from the Special Olympics in Washington. A teaching manual can be found at the Unified Robotics website, and its 2016 season is from Oct. 1 through Dec. 3.

The Robotics Education and Competition Foundation (REC) also welcomes students with special needs to the global VEX IQ Challenge, VEX U activities and VEX Robotics Competition, the world’s largest robotics competition.

“Each program offers a unique experience to design, build and program a robot for competition,” says Vicki Grisanti, senior director of communications and community relations for REC. “We accommodate students with special needs at our events by encouraging anything from noise-canceling headphones, if noise is a concern, to offering students parental support during the judging process.” The foundation strives to maintain an inclusive environment to meet the needs of all students participating, Grisanti says.

For children with special needs, technology is becoming more than just entertainment — it is evolving into a game changer in learning and development. Parents, researchers and engineers hope that one day soon a wide range of options will be available to parents and students at every school, not only to ensure that these students’ educational needs will be met, but to evolve students’ life skills in ways we are still discovering are possible.